I am currently visiting my parents. Although they no longer live in the house (or even the state) in which I grew up, they are big book-hoarders and still have many of the books my sisters and I cherished as kids.

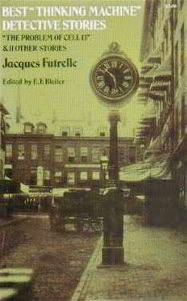

When I come here I like to dig out a few of my old favorites to stack up on the little bedside dresser in the back room where I sleep. On top of my current stack is the small volume pictured at left, a 1973 Dover paperback collection of Jacques Futrelle's most popular "Thinking Machine" detective stories.

My parents both love mystery stories; our house is packed with Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, Ngaio Marsh, A. Conan Doyle, Rex Stout, Mary Stewart, and on and on. I first encountered Futrelle and his character Professor Augustus S.F.X. Van Dusen, a.k.a. The Thinking Machine, when I was about eleven. One of our local beleaguered California public schools had closed, and they were just giving away books. My mother drove down there in our blue Honda Accord hatchback and loaded it up with textbooks, including several hardback 9th and 10th-grade readers.

One of these readers contained Poe's "The Murders in the Rue Morgue", Connell's "The Most Dangerous Game", and Futrelle's "The Problem of Cell 13" (all links are to free full texts). I read the book over and over, and I loved Futrelle's story so much that one or both of my parents dug around in their boxes full of mysteries and came up with Best "Thinking Machine" Detective Stories: "The Problem of Cell 13" & Other Stories.

Fans of Gregory House may well have been Augustus S.F.X. Van Dusen fans first. My fascination with the irascible genius probably gave me a higher tolerance for brilliant assholes during my youth than was quite healthy, but I still love these stories. Below the fold is a taste of "The Problem of Cell 13" and an excerpt from "The Thinking Machine":

"Nothing is impossible," declared The Thinking Machine with equal emphasis. He always spoke petulantly. "The mind is master of all things. When science fully recognizes that fact a great advance will have been made."

"How about the airship?" asked Dr. Ransome.

"That's not impossible at all," asserted The Thinking Machine "it will be invented some time. I'd do it myself, but I'm busy."

Dr. Ransome laughed tolerantly.

"I've heard you say such things before," he said. "But they mean nothing. Mind may be master of matter, but it hasn't yet found a way to apply itself. There are some things that can't be thought out of existence, or rather which would not yield to any amount of thinking."

"What, for instance?" demanded The Thinking Machine.

Dr. Ransome was thoughtful for a moment as he smoked.

"Well, say prison walls," he replied. "No man can think himself out of a cell. If he could, there would be no prisoners."

"A man can so apply his brain and ingenuity that he can leave a cell, which is the same thing," snapped The Thinking Machine.

Dr. Ransome was slightly amused.

"Let's suppose a case," he said, after a moment. "Take a cell where prisoners under sentence of death are confined--men who are desperate and, maddened by fear, would take any chance to escape--suppose you were locked in such a cell. Could you escape?"

"Certainly," declared The Thinking Machine.

"Of course," said Mr. Fielding, who entered the conversation for the first time, "you might wreck the cell with an explosive--but inside, a prisoner, you couldn't have that."

"There would be nothing of that kind," said The Thinking Machine. "You might treat me precisely as you treated prisoners under sentence of death, and I would leave the cell."

"Not unless you entered it with tools prepared to get out," said Dr. Ransome.

The Thinking Machine was visibly annoyed and his blue eyes snapped.

"Lock me in any cell in any prison anywhere at any time, wearing only what is necessary, and I'll escape in a week," he declared, sharply. Dr. Ransome sat up straight in his chair, interested. Mr. Fielding lighted a new cigar.

"You mean you could actually think yourself out?" asked Dr. Ransome.

"I would get out," was the response.

"Are you serious?"

"Certainly I am serious."

Dr. Ransome and Mr. Fielding were silent for a long time.

"Would you be willing to try it?" asked Mr. Fielding, finally.

"Certainly," said Professor Van Dusen, and there was a trace of irony in his voice. "I have done more asinine things than that to convince other men of less important truths."

The tone was offensive and there was an undercurrent strongly resembling anger on both sides. Of course it was an absurd thing, but Professor Van Dusen reiterated his willingness to undertake the escape and it was decided on.

From "The Thinking Machine" (link to full text from futrelle.com), the story that explains where Professor Augustus S.F.X. Van Dusen got his nickname:

There was a little murmur of astonishment when Professor Van Dusen appeared. He was slight, almost child-like in body, and his thin shoulders seemed to droop beneath the weight of his enormous head. He wore a number eight hat. His brow rose straight and dome-like and a heavy shock of long, yellow hair gave him almost a grotesque appearance. The eyes were narrow slits of blue squinting eternally through thick spectacles; the face was small, clean shaven, drawn and white with the pallor of the student. His lips made a perfectly straight line. His hands were remarkable for their whiteness, their flexibility, and for the length of the slender fingers. One glance showed that physical development had never entered into the schedule of the scientist’s fifty years of life.

The Russian smiled as he sat down at the chess table. He felt that he was humouring a crank. The other masters were grouped near by, curiously expectant. Professor Van Dusen began the game, opening with a Queen’s gambit. At his fifth move, made without the slightest hesitation, the smile left the Russian’s face. At the tenth, the masters grew intensely eager. The Russian champion was playing for honour now. Professor Van Dusen’s fourteenth move was King’s castle to Queen’s four.

“Check,” he announced.

After a long study of the board the Russian protected his King with a Knight. Professor Van Dusen noted the play then leaned back in his chair with finger tips pressed together. His eyes left the board and dreamily studied the ceiling. For at least ten minutes there was no sound, no movement, then:

“Mate in fifteen moves,” he said quietly.

There was a quick gasp of astonishment. It took the practised eyes of the masters several minutes to verify the announcement. But the Russian champion saw and leaned back in his chair a little white and dazed. He was not astonished; he was helplessly floundering in a maze of incomprehensible things. Suddenly he arose and grasped the slender hand of his conqueror.

“You have never played chess before?” he asked.

“Never.”

“Mon Dieu! You are not a man; you are a brain—a machine—a thinking machine.”

“It’s a child’s game,” said the scientist abruptly. There was no note of exultation in his voice; it was still the irritable, impersonal tone which was habitual.

This, then, was Professor Augustus S. F. X. Van Dusen, Ph. D., LL. D., F. R. S., M. D., etc., etc., etc. This is how he came to be known to the world at large as The Thinking Machine. The Russian’s phrase had been applied to the scientist as a title by a newspaper reporter, Hutchinson Hatch. It had stuck.

Shakesville is run as a safe space. First-time commenters: Please read Shakesville's Commenting Policy and Feminism 101 Section before commenting. We also do lots of in-thread moderation, so we ask that everyone read the entirety of any thread before commenting, to ensure compliance with any in-thread moderation. Thank you.

blog comments powered by Disqus