Sunday night was the first half of the two-part premiere of Better Call Saul, the Breaking Bad spin-off prequel documenting the rise of dirty attorney Saul Goodman. Last night, the second half aired. And OMG THIS SHOW.

We are two episodes in, and I'm already remembering how Vince Gilligan turned me into an anxious, wrung-out, shitshow mess during the final season of Breaking Bad, lol. I mean.

Honestly, despite all attempts to temper my expectations for Better Call Saul, I had really high hopes going in, mainly because of this article. I knew that Gilligan & Co. were working really hard to deliver a great product, and I trusted that they would.

I didn't expect—or want—this show to be Breaking Bad: Part 2. I expected and hoped that it would be its own thing—a cousin of Breaking Bad, rather than a replica. And Gilligan has achieved precisely that: Better Call Saul has enough references to Breaking Bad to feel like it exists in the same universe, but is distinct and original enough to stand on its own. And to capture my attention of its own accord.

In the Guardian, Richard Vine described it as New Order to Breaking Bad's Joy Division, and that is a perfect description.

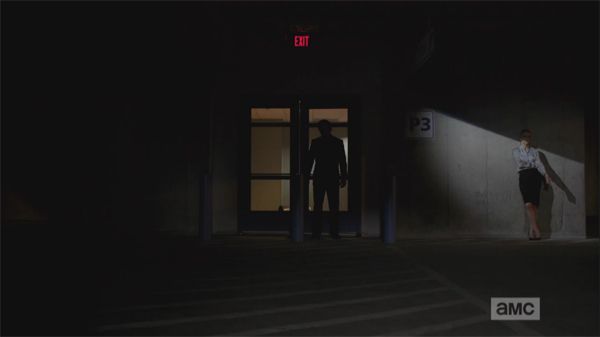

Of course I loved seeing Mike and Tuco—familiar characters we met through the prism of Walter White's terrible life—and I love all the thematic similarities (Saul's own random crappy car: a Suzuki Esteem), and I love the callbacks to familiar imagery in Breaking Bad (the battered reflective trash can on which Saul unleashes his frustration, mirroring the battered reflective wallmount paper towel dispenser on which Walt unleashed his), and I love the aesthetic continuity between the two shoes, which is always compelling, and gives us gifts like this memorable shot.

But mostly I just love this origin story. Every piece of it, from the black and white scene of Saul's present life—being lived, as he predicted, as a manager of a Cinnabon in Omaha—to his vibrantly colored past, where he is not even yet Saul Goodman, but Jimmy McGill, a struggling lawyer who is trying, and failing, to build a practice that will make him a living.

He is hustling for paying clients, and meanwhile spending his time as a public defender, for $700 a defense. He is obliged to defend three rich white teenage boys, on trial for mutilating and sexually violating a corpse (which we don't know until later), and here the show provides us with a searing commentary on the dirty work Saul was doing even when he was a clean lawyer.

"Oh, to be 19 again. Are you with me, ladies and gentlemen? Do you remember 19? Lemme tell ya—juices are flowing, the red corpuscles are corpuscling, the grass is green and soft and summer's gonna last forever. Now do you remember? Yeah you do. But, if you're being honest—I mean, really honest—you'll recall that you also had an underdeveloped 19-year-old brain. Me personally? If I were held accountable for some of the stupid decisions I made when I was 19, oh boy, wow. I bet if we were in church right now, I'd get a big AMEN!"It is then the prosecutor plays the video of the young men's crime, and we are invited to judge this horror against the flippant "boys will be boys!" defense mounted by Saul. Who could barely deliver it, without looking ashamed.

Crickets.

"Which brings us to these three. Now, these three knuckleheads—and I'm sorry, boys, but that's what you are—they did a dumb thing. We're not denying that. However, I would like you to remember two salient facts: Fact One: Nobody got hurt. Not a soul. Very important to keep that in mind. Fact Two: Now the prosecution keeps bandying this term 'criminal trespass.' Mr. Spinozo, the property owner, admitted to us that he keeps most portions of his business open to the public both day and night, so."

Dubious shrug.

"Trespassing? Eh, it's a bit of a reach, don't you think? Here's what I know: These three young men, near honors students all, were feeling their oats one Saturday night, and they just went a little bananas. I dunno. Call me crazy, but I don't think they deserve to have their bright futures ruined by a momentary, minute, never-to-be-repeated lapse of judgment. Ladies and gentlemen, you're bigger than that."

Later, when he collects his public defender's fee from the court clerk, he complains about how little he's being paid. "They going to jail, ain't they?" she asks him. "So?! Since when does that matter?! They had sex with a head!" he exclaims in return. He has contempt for his court-appointed clients, because they are utterly contemptible.

Nothing in Saul's life is making him happy. Not his clients, not the paltry sums he makes for defending them, not his car, not his tiny office in the back of the pedicurist he once recommended to Walter White as a money-laundering front, and not that his older brother's law firm is taking advantage of the fact that his brother (played by the terrific Michael McKean) is ill—and lives in a self-imposed exile away from electromagnetic devices which he believes has made him sick.

Saul has to walk a fine line between not infantilizing his brother or auditing his experience with the reality that his brother's illness is a psychological one, and may be compromising his future and his ability to support himself.

That's certainly not a theme I expected from the show, and, so far at least, I think the show is handling it well.

To add insult to a multitude of injury, Saul's own brother suggests that he not use his given name, Jimmy McGill, because his brother's last name is part of the successful firm name, and Saul should make his own way and not ride on others' coattails. Even his very identity is not his own, and not within his control.

And so begins the journey of Saul Goodman.

Already, he has had a harrowing encounter with the unpredictable and vicious Tuco, where we see (again) that Saul Goodman's most valuable asset is (and has always been) his ability to think fast and talk even faster.

"You've got quite a mouth on you," Tuco tells him, after Saul negotiates his freedom.

"Thank you," Saul replies.

That mouth will no doubt be the thing that gets him into trouble, and the thing that gets him out of trouble, in equal measure. And I will happily go along for the ride, shrieking and curling into a ball and gritting my teeth with anxiety, as I can barely stand to look but definitely can't look away.

I can't begin to remember what I thought about Breaking Bad, and where it would go, after two episodes, so I won't make predictions about Better Call Saul. Even though we know where it's headed, I have no idea how it will get there.

My impression, though, is that, if Breaking Bad was the story of a man who made all the wrong choices, Better Call Saul may be the story of a man who was left with no good ones.

Shakesville is run as a safe space. First-time commenters: Please read Shakesville's Commenting Policy and Feminism 101 Section before commenting. We also do lots of in-thread moderation, so we ask that everyone read the entirety of any thread before commenting, to ensure compliance with any in-thread moderation. Thank you.

blog comments powered by Disqus