[CN:Racism, sexism, gun violence, disablist language. This is part three in a four-part series analyzing Bernie Sanders' political history through an intersectional feminist lens, asking questions about the role privilege has played in that development. Previously in this series: Looking for Bernie, Part 1: Sanders '72 and Looking for Bernie, Part 2:Mr. Sanders Goes to Burlington.]

PART 3: SANDERS '90

As far back as 1972, Sanders had been told that he should be running for Congress, not for governor, because of his interest in national policy and foreign affairs. In 1988, he revisited that advice. Vermont's Senator Robert Stafford retired; Congressman Jim Jefford chose to run for his seat rather than for re-election to the House of Congress. Sanders decided to run. As he writes in his autobiography, Outsider in the House:

I began the race as a "spoiler." (Oh how I love that word, with its implications of the sacrosanct nature of the two-party system.) Would I take away enough votes from the Democrat to elect the Republican? But a funny thing happened on the way to Election Day. I wasn't the spoiler, after all. The Democrat was.Sanders lost the race to Republican Peter Smith—but only by 3.5%. His Democratic opponent came in third—a distant third at that. It was a victory, of sorts, for Sanders, shaking up the Vermont party system and raising the previously preposterous idea that he might get into national office. He was no longer the 1970s radical running "educational" campaigns. He'd learned to make nice with business in Burlington, and to fashion his campaigns around voter concerns, rather than the other way around. He had become quite a skilled and canny politician, who could do deals when he needed to.

In his autobiography, Sanders explains that he weighed a number of options for 1990, including a possible gubernatorial run, since Madeleine Kunin decided not to stand for a further term that year. He decided instead that he had a chance to unseat Smith, based on his good showing in 1988, and also because the Savings and Loan scandal was tarnishing the reputation of both parties in Congress. All that makes sense.

But I also think there may have been another factor involved: Sanders and the Vermont Democrats came to a truce. I don't know if it was explicit or implicit in 1990. But the facts are that the Democrats gave approximately zero support to Sanders' Democratic opponent in 1990. Upon his election, Sanders caucused with the Democrats. By 2005, Howard Dean was describing Sanders as basically a liberal Democrat, who voted with the Democratic Party "98% of the time." (Link goes to a YouTube clip of Dean saying this on Meet the Press. I've seen that percentage thrown around with no context; it seems to be just Howard Dean's offhand remark, not an actual figure based on statistical analysis.)

I doubt Sanders appreciated Dean's downplaying of his socialism, but Dean's remarks provide insight into how the Vermont Democratic Party came to view Sanders: he might be formally outside the party structure, but in practice things are different. One way or another, he hasn't had to worry about a strongly supported Democratic challenger for some time. In 1994, 1998, 2000 and 2002, no Democratic candidate opposed Sanders for Congress. Sanders ran in the Democratic primary in 2006, but declined the Democratic nomination in order to run as an Independent for Senate. The years when Democratic candidates did run, their lackluster performances suggest a distinct lack of support from the party. And the first candidate to feel that lack of support, unfortunately, was Dolores Sandoval, one of the most innovative and interesting political voices I heard during the course of this research.

In 1990, Dr. Dolores Sandoval was a university professor who had actively served on various statewide committees to women's issues, civil rights, and education. She was also the first African-American woman in Vermont to run for a statewide office. And if you can't figure out why that was significant, consider: at that time, only 25 black Americans sat in Congress. Only 63 black Americans had ever served in the House, and only 3 had served in the Senate. (Today there are 46 black members in the House and 2 in the Senate.) There were only 31 women in Congress in 1990; today there are 104. Only 5 African-American women had ever sat in Congress; in 1990, only one of them, Cardiss Collins, was currently serving. Today, there are 18 black women serving in Congress.

Sandoval was more than a mere statistic; she was an accomplished academic with genuinely fresh, and indeed, radical ideas (more on those later). I don't know what would have happened had she been elected, but a look at her LinkedIn profile suggests a pretty amazing CV. In addition to teaching in Africa, Middle East & Latin American Studies, she served in a variety of university administrative roles, held fellowships around the world, worked on land mines issues in Sierra Leone and around the world, worked on aid for Honduras, and pursued research on immigrants as well as founding the Da costa-Angelique Institute ("Canada's first black think tank") and Museum-Observatory of Immigration. Oh, and she's a playwright. And those are just some highlights.

My point is, Sandoval would not only have been a historic Congressional representative; she would have likely pursued many important progressive concerns with vigor, creativity, and thoughtfulness. Would that have made for a good politician? I can't say. But if you wanted to pick the outsider, the real fresh perspective in 1990, it would have been Sandoval, not Sanders.

We'll never know how that might have worked out. From the start, the Democratic Party was unsupportive. Thanks to a financial dispute between Sandoval and Peter Freyne, a local journalist who worked on her campaign for a time, there is a record of documents submitted to the FEC about her campaign and the 1990 election. And they make it clear that the state Democrats weren't planning any real opposition to Sanders. He might have run as an "Independent," but that doesn't mean he got equal opposition from both left and right.

As early as March, 1990, according to Sandoval, the Chair of the Vermont Democratic Party, Violet Coffin, was discouraging her from running because of the "strength of the Socialist candidate." In a March 29 letter to Coffin, Sandoval also protests the remarks of party executive director Craig Fuller, who had described the Democratic primary candidates as weak, which, as Sandoval wrote in her letter, "shut the gate after the first two male candidates emerged." Several democrats demanded that Fuller lose his position, but as an April1, 1990 story in the Burlington Free Press notes, he kept his job.

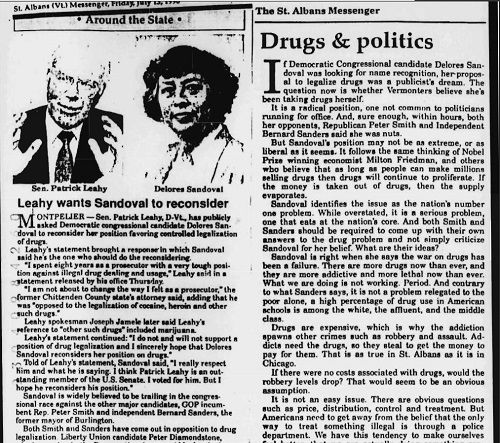

Later in the race, Madeleine Kunin and Senator Patrick Leahy claimed that their lack of support for Sandoval was a result of the opinions she expressed that summer about drugs and the Middle East. But the lack of support for Sandoval was clear to Vermonters as early as April. A column by Emerson Lynn in the St. Albans Messenger states:

Kunin has repeatedly stated that one of her priorities is to get other women to run for office. She says she wants to help them. But her support comes at a price: she has to think the woman can win.I'd be tying Occam's Paisley tie into a big Windsor if I didn't add the obvious: Sandoval was considered a "weak" candidate because of her race and gender, in part if not in whole. Would it be difficult for a black woman to get the votes of white Vermonters? Sure. Sandoval faced prejudices a white man, or a white woman, didn't have to face. But the only way to get more people of color elected into office is... to get more people of color elected. And that would take a lot of work and support than the Democrats were willing to give Sandoval in 1990, running against Sanders. As Sandoval wrote in a statement to the FEC:Such thinking helps erode the strength of the two-party system. It is a self-fulfilling prophecy of decline... Obviously Kunin would drive a wedge into the Sanders campaign if she were to declare steadfast support for Sandoval. Any support Sandoval gets will come at the expense of Sanders. But what do Democrats get if Sanders wins? Is it truly a victory for Democrats to get Peter Smith out of office when Sanders beats up on Democrats as often as Republicans?

Clearly, the records shows that the first time a Black candidate gained sufficient voter support to be recognized as the Democratic Party's candidate for the US House of Representatives all usual support efforts and recognition were withheld from her.Okay, so what does all of this have to do with Bernie Sanders? Sandoval did not include charges of racism or sexism against him in her FEC counter-complaints about Freyne and the Vermont Dems. (She took plenty of jabs at him on the campaign trail, of course. An example: an April speech questioning Sanders' "patronizing attitude" about her chances, asking "Is that because he thinks this woman candidate is a pushover?")

And, it is very important to note that Sandoval today says good things about Sanders. "It's always been my impression he's been good on racial issues," she's reported to have said in a July 1, 2015 story in the Vermont alternative magazine Seven Days. Sandoval praises his 2002 Iraq War vote, calling the war "a racist endeavor." Whatever discrimination she experienced in 1990 from Vermont Democrats has not left her with bitterness towards Bernie Sanders, and I want to make that clear.

Sanders himself hasn't said much about that discrimination, only noting in his book that Sandoval "ran a weak campaign with very little party support." That's an understatement, to say the least! It's probably a good way to keep from calling his white Vermont Democratic allies racists, though. Sanders still has criticisms of the party system but he's no longer Sanders '72 when it comes to the Democrats. There's been a bit more than just a détente between Sanders and Vermont Dems. Rather, it's been closer to an entente cordiale. Sometimes quite cordiale, indeed.

And Sanders '90 left Sanders '72 behind in other ways as well, when he took a rightward drift on the topics of drugs, war, and guns.

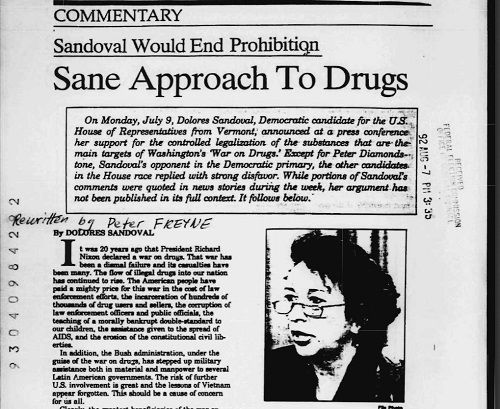

Let's start with drugs. That summer, Sandoval called for their controlled decriminalization. In one of her most detailed comments on the issue, a July 15, 1990 commentary piece for the Sunday Rutland Herald and the Sunday Times Argus, she cited the violence bred by illegal markets and a frightening decline in civil liberties as good reasons to end the War on Drugs. While Sandoval says she does not personally condone drug use, she urged a controlled legalization in place of the current prohibition. Suggesting that drugs are actually made more enticing by their verboten status, she writes, "I believe that if we rid out society of the forbidden-fruit glamorization of drugs, we will be serving the best interests of our rebellious youth." She also decries the ineffective use of incarceration to fight addiction: "Quite simply, I believe drug addiction should lead to the clinic door, not the jailhouse door."

If any of this sounds familiar, it should. Remember Sanders' 1972 letter that's been (falsely) hailed as supporting full marriage equality? It called for the decriminalization of laws relating to homosexuality, as well as those relating to drugs, among others. And in a campaign speech on October 1972 reported in the Bennington Banner, he explicitly called for the adoption of "the British system, in which heroin users are given the drug free from clinics, thereby reducing crime and other social problems resulting from the high cost of illegal drugs."

But Sanders 1990 is another story. Both Smith and Sanders expressed strong disagreement with Sandoval. A July column in the Burlington Free Press says "Sanders worries that legal drugs would become cheaper traps locking the impoverished in ghetto squalor." ("Ghetto squalor"? I really, really hope that's not a direct quote.) The Press goes on to gaslight Sandoval for calling out the racist stereotypes invoked by such a response, but the St. Albans Messenger was friendlier to her. In a July 10 column, Emerson Lynn writes that "contrary to what Sanders says, it is not a problem relegated to the poor alone." If Smith and Sanders didn't like Sandoval's ideas, Lynn argued they needed to come up with better answers.

All this might be a pretty small footnote; Sanders changed his mind, and expressed it in grating terms that invoke classist and racist stereotypes. Surprise! He's a politician. But drugs are another area where certain Sanders fans have misrepresented his record in order to paint him as an omniscient progressive messiah. Here is Vox magazine holding up his 1972 letter as some kind of proof that Bernie Sanders has always been right (meaning "left") on the drug war. No, no, and no. 2015 Sanders is actually much closer to 1990 Sanders, cautiously suggesting that we need to look at the medical decriminalization of marijuana before committing to a policy view. Sorry, Vox, but the Washington Post has a far more accurate headline: "On marijuana, Bernie Sanders is kind of a disappointing socialist ex-hippie."

July saw Sandoval make another bold policy suggestion: a call to radically alter US policy in the Middle East, in response to President Bush's decision to suspend talks with the PLO. As described in July 19 campaign material, she said the US should end all military aid to Israel until it came to the table with the Palestinians, and impose further sanctions should there be no negotiations for a peaceful resolution within 30 days. She calls out Sanders for condemning human rights abuses in Central America and in China, but for being "silent about human rights abuses and the threat of mass slaughter in the Middle East." In September, a Times-Argus story by Debbie Bookchin records her as opposing Bush's airlift to Saudi Arabia, which had come in response to the Iraq invasion of Kuwait. By contrast, "Smith supported the president's actions, and Sanders supports a limited deployment."

To be fair to Sanders, his record in Congress of opposing George H.W. Bush's Gulf War certainly paints him as more of a peace-seeker than a war-monger. And talking about Israel is difficult for plenty of people on the left, but it can be especially complicated for Jewish politicians in the U.S. (I'm not going to link to any of it, because fuck that, but suffice to say, the dankest anti-Semitic corners of the Internet have plenty of hateful shit to say about Bernie Sanders and Israel. And those hatemongers can go to straight to hell, preferably by overnight express.)

So I don't know that Sandoval's ideas were necessarily ideas that all progressives could have gotten behind, or would support today. But it must be said that Sandoval, not Sanders, had the radical idea about Middle East policy in 1990. Sanders would continue to go on to have a pragmatic and selective view of military deployment and defense spending, but more about that later. Because I want to round out 1990 considering Sanders, Smith, and guns.

Peter Smith, who had squeaked out a win against Sanders in 1988, was a fairly liberal Republican. In a July 29 piece in the Chicago Tribune, George E. Curry put it like this:

Smith's vote has been increasingly liberal in his two years in Congress. He has scored high with voters for his position on fiscal issues and has a better rating than Sanders on education issues.In his autiobiography, Sanders describes Smith's problems with the NRA:He shares Sanders' criticism of the Bush administration's handling of the savings and loan crisis. But Smith also has supported some gun-control legislation, which has angered the NRA.

A few months after taking office, Smith suddenly announced that he would vote for the ban on assault weapons [ed.—that he had opposed in 1988] The NRA and other elements in Vermont's sportsmen community were furious at his about-face. They felt betrayed and worked hard to defeat him. While the NRA has never endorsed me or given me a nickel, their efforts against Smith in 1988 [sic—1990] clearly helped my candidacy. (I should add here that in 1992, '94, and 96, the NRA strongly opposed me.)To be clear: in 1990, Sanders ran to the right of Smith on gun control. And Smith lost. In a 1991 story for the Vermont Times, Kevin J. Kelly asked why Sanders, along with Vermont's other two Congressmen, opposed the Brady Bill. He reported that:

...Sanders' announced opposition to the Brady proposal seems especially incongruous. The independent socialist has said that, among his House colleagues, he feels politically closest to the members of the Congressional Black Congress. And only one of Sanders' 25 black colleagues is pledged to vote against the Brady bill.I'll bet he didn't.Sanders himself did not respond to a request for an interview on this issue.

His spokesperson, Anthony Pollina, claimed that Sanders was representing "all Vermonters," including many who were hunting enthusiasts. I am quite sure that's true. But the rest of his response, as relayed by Pollina, is straight up bullshit:

Sanders believes many politicians will use the Brady bill as a "smokescreen," Pollina suggested. Bernie would rather work with Congress to develop a package of legislation that deals with the root causes of crime, such as economic injustice and the lack of job opportunities in many urban communities, the aide explained. Simply voting for the Brady bill and not addressing poverty as a cause of violence could be seen as "dishonest," Pollina said.So, the root cause of gun-related crime is a lack of jobs in "urban" communities. I see what you're doing there, and I'm not impressed, Bernie.

Suffice to say, when a legislator from largely white, rural state starts going on about "urban crime" as an excuse for not embracing gun control measures, it sounds like lazily using a pretty racist stereotype to me. As if gun violence wasn't a problem in rural areas, or amongst employed people. But mostly, I'm baffled that it's apparently impossible to both enact gun control and pursue better jobs policies at the same time. What? (Next investigative exploration: Does Bernie Sanders have a walking-and-chewing-gum problem? I kid, I kid.)

It's also noteworthy that in the same article, Peter Smith charges that the NRA played more than a passive role in helping to elect Sanders; he claims that they actively urged Vermonters to vote for Sanders in radio and TV spots. That contradicts Sanders' memories in his autobiography. Without access to more archival evidence, I can't say who was right. And Smith, of course, would have had reasons to misremember. But perhaps Sanders might also be misremembering exactly how the election went down.

And while it's true that the NRA has subsequently turned against Bernie Sanders, repeatedly, let's recall that they're the fringe of gun control opponents these days. No-one has ever accused Bernie Sanders of being a Tea Party type, as far as I know. But anyone claiming that Sanders is the only "progressive" choice needs to remember that even if the NRA doesn't love him, his stance on guns is still a social justice problem, and it puts him to the right of many Democrats.

So what does his overall record in Congress look like on guns? Well, the Slate headline "Bernie Sanders, Gun Nut" isn't really fair. (It's hard to be a "gun nut" when you don't own a gun, which Sanders doesn't.) And votes are only one part of a politician's stance on anything. Having said that, what do the votes actually say?

VoteSmart has a record of Sanders' key votes on gun control. Looking solely at this data, I'd say Sanders has about a dozen votes that most progressives would be on board with, a few that are a bit mixed (in part because the bills were obviously results of compromises), and 7 that most progressives would recoil in horror at. Sanders has been generally good in prohibiting the sale of assault weapons and limiting magazine capacities, and also has been good on restricting the carrying of concealed weapons across state lines. He has also voted for at least one major safety regulation (The Trigger Lock Amendment of 2006), and has resisted efforts to shrink the background check time. (That's important because if the FBI can't complete a background check in time, the default by federal law is to allow the purchaser to buy the gun.) Not included in these votes, but worth a mention, is Sanders' consistent support for VAWA.

On the mixed side of things, he's voted for minimum sentences for federal crimes carried out with a gun; many progressives have problems with mandatory sentencing laws. Others might agree with the intent of reducing gun use. I think most progressives would agree with Sanders' 2009 Health Care Bill Amendment vote, which touches on guns only briefly in that gun ownership can't be used to affect healthcare coverage. Maybe the most mixed bill, 2006's Washington DC Voting Act, gives Washington representation in Congress—good!—but horribly guts its gun laws—terrible.

As for the bad, it is quite bad. Sanders voted against the Brady Bill twice, as well as against background checks for gun show purchases. (He later supported a bill to close that loophole, however.) He supported a law that limited Indigenous Health Bill funds from being used for any "anti-gun" purpose whatsoever, such as gun buy-backs or any program that would certain funds from being used to reduce gun ownership. He voted to allow loaded guns in National Parks, which is a terrible idea. (Unfortunately, that terrible idea is now law.) And Sanders voted twice to protect firearms manufacturers from legal liability for gun violence.

That last has been in the news lately. Two parents who lost their child in the Aurora massacre lost their lawsuit and have been ordered to pay damages, thanks to the bill Sanders supported. And Sanders did some pretty shitty 'splaining when a gun control activist challenged him to defend those votes:

"With all due respect, you also cast the vote to allow gun manufacturers to never be sued," Laszlo interjected.And you know, that would be an extremely relevant point! If, that is, someone could use a baseball bat to kill 12 people and wound 70 more in a mere matter of minutes."Right I did, OK?" Sanders fired back, adding later, "Why would I have voted that way? Because if somebody has a gun and somebody steals that gun and they shoot somebody with it, do you really think it makes sense to blame the manufacturer of that weapon? If somebody sells you a baseball bat and somebody hits you over the head with it, you're not going to sue the baseball bat manufacturer."

Unfortunately, Sanders had more 'splainy things to say:

"I come from a state that has virtually no gun control and it turns out one of the safest states in the country... I understand that guns in my state are different than guns in Chicago or Los Angeles," Sanders said. "People in urban America have got to appreciate that the overwhelming majority of people who hunt know about guns and respect guns, and are law-abiding people, that's the truth. And people in rural America have got to understand that in an urban area, guns mean something very, very different."Ouch. I don't think people in "urban America" need to be lectured about their understanding. And the law-abiding rural states versus criminal cities? It's true Vermont has a low rate of gun violence (though guns are still a problem, according to domestic violence advocates). Gun violence is complicated. And the top five states for gun deaths are very rural: Louisiana, Mississippi, Alaska, Wyoming, and Montana. As for "law-abiding" gun owners, I guess the police would be the most law-abiding of all? Ah, whoops.

The language of gun violence is brimming with racist stereotypes, and anyone who talks seriously on the topic needs to be aware of that. It can't be de-racinated just because one wants it to be. But, as described by his old friend Richard Sugarman, Sanders seems determined to ignore the racial aspects of gun-talk. He's intractable in his views:

"He doesn't have a gun," says his close friend Richard Sugarman, a religion professor at the University of Vermont, when I asked how Sanders—a University of Chicago graduate from Brooklyn—became a Second Amendment guy. "He doesn't really care about guns. But he cares that other people care about guns. He thinks there's an elitism in the antigun movement."An "elitism"? Sure. The Congressional Black Congress is very elitist. People who want students to be safe in their classrooms are very elitist. But protecting the rights of white men is definitely not? Once again, Sanders' unacknowledged white male privilege is a real problem; he thinks he shouldn't even be questioned on guns:

Sanders' loquaciousness has its limits. When the conversation shifts away from bread-and-butter economic issues, his answers become curt. On the issue of gun violence, he is particularly tight-lipped. Indeed, he refused to grant an interview to Seven Days on the subject for two and a half months after last December's deadly school shooting in Newtown, Conn.(If you have any doubt that white male privilege is relevant to Sanders' success, by the way, imagine the words that might be used to describe a woman of color who responded to questioning like that.)...Asked whether he'd vote for an assault-weapons ban if it reached the Senate floor, he said, "We'll see. We'll see what other things it is part of."

Asked why he was on the fence about the assault-weapons ban, which he backed in 1994, Sanders interrupted midsentence, saying, "This is not one of my major issues. It's an issue out there. I've told you how I feel about it. If there's anything else you want to ask me about, I'm happy to answer. But that's about it."

Five minutes after the gun discussion had begun, Johnny One-Note wanted to get back to tax policy and economic disparity.

In addition to his gun votes, of course, Sanders' time in Congress has left him with plenty of votes to be clearly proud of. You can read On the Issues coverage of Sanders, or GovTrack on Sanders, or Ballotopedia, among other analyses. He's tended to vote strongly in favor of abortion rights, preventing workplace discrimination, protecting the environment, expanding healthcare access, voting rights, stopping employment discrimination against women and men of color, economic stimuli, more equitable taxes, protecting public schools and Social security, among other things. But what does Sanders himself think are his most important votes? Well, one clue is the Sanders campaign website. At the bottom of the page, there's a timeline by decade about Bernie, and the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010 provide highlights. I can't think of a fairer way to estimate how he sees his own career (or at least, how he and his campaign want us to see it,) so take a look for yourself.

Since getting elected in 1990, Sanders has proved canny, very canny, at figuring how to be just as progressive as his Vermont electorate will let him be. He's learned to compromise, often in a rightward direction. Does that bode well for his presidential run? As usual, it depends on your perspective. (Spoiler: Sanders '72 would probably hate it.) Tomorrow, in "Looking For Bernie, Part 4: Turning Right Towards 2016," I'll again use an intersectional feminist lens for a closer look at some of the places he's compromised, re-prioritized, or just plain dodged the question when it comes to same-sex unions, immigration, and environmental racism.

[Commenting Note: The commenting policy is in full effect. There are no exceptions.]

Shakesville is run as a safe space. First-time commenters: Please read Shakesville's Commenting Policy and Feminism 101 Section before commenting. We also do lots of in-thread moderation, so we ask that everyone read the entirety of any thread before commenting, to ensure compliance with any in-thread moderation. Thank you.

blog comments powered by Disqus